Gertrude Stein is annoying.

Retelling Gertrude Stein is liberating.

Lionizing Gertrude Stein is troubling.

Can Gertrude Stein be retold without the trouble?

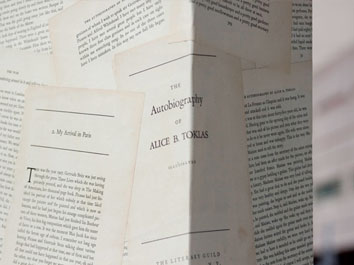

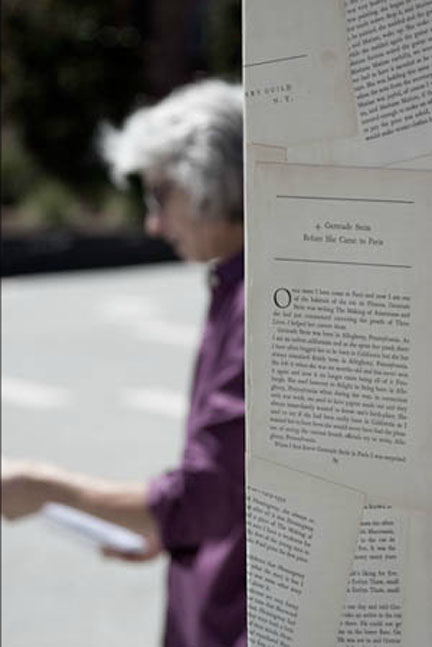

84” H x 36” W x 18” D

213 cm x 91 cm x 46 cm

wood, glue, book pages

Readings and Object

5 September 2011

In Jessie Square, in front of the museum

In response to “Seeing Gertrude Stein / Five Stories”

An exhibition at the Contemporary Jewish Museum

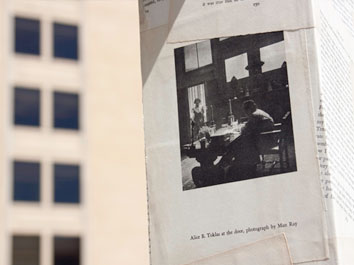

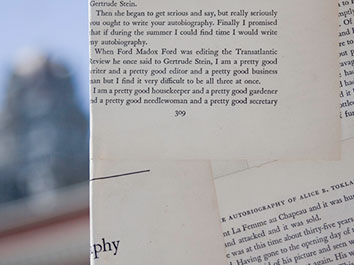

Stein was 5’1″, as is the “I”. Atop the Picasso pedestal she towers over the world at seven feet. The front and two sides of the “I” are sheathed with pages from The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, published in 1933. The back side is open, leaving the interior of the “I” visible: unfinished construction-grade plywood with flaws, manufacturer’s stamp, knots, etc. The pedestal is covered with images of Picasso’s work prior to 1933, including his portrait of Stein.

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is ``a wonderful self-portrait of a perfect egoist.``

New York Herald Tribune, 1933

``Somehow, before one has read three pages one is under the shadow of the letter I. ’I’ stands in the foreground of the novel; a stalwart figure, well proportioned, but dominating the view. Behind him one may catch a glimpse of a tree or a town; but not for long. `{`The author`}` returns methodically, persistently, with a devotion that is impressive to the fact of himself.``

Virginia Woolf, 1929

``The other of Simone de Beauvoir’s existentialist feminism and of Said’s orientalism is not another self, but one whose selfhood is denied in the interest of securing the centred `{`sic`}` subject’s own soaring ego.``

Andermahr et al., 2000

``To take seriously Stein’s divulgence ‘I'm always wanting to collaborate,’ however, is to see that in the collaborative arena, particularly the theater, she left the door open for artists to continue working with her; indeed, she invited them to do so. What Stein calls ’genius,’ moreover, is produced by, and productive of, relations. Stein produced, in addition to art, literature, theater, dance, and music, a web of international and interdisciplinary alliances, new schemas of kinship, new narratives of cultural value.``

Tirza True Latimer, 2011

``If the exploitation of man by man has found its shameful expression in the conduct of business, we have, up to now, rarely seen the application of this principle to the domain of art in the unexpected form of the exploitation of ideas. The memoirs of Miss Toklas furnish us with an opportunity to appreciate how far the limits of indecency can be pushed.``

Tristan Tzara, 1935

```{`Deborah`}` Kass’s adoption of images already resonant in contemporary lesbian and feminist cultures demonstrates how reproducing images may critique as well as create alternative personal and historical narratives....This is a lesson learned from Stein, who understood well how images help to create a public profile, generate artistic communities, and form alternative family albums and family trees.``

Tirza True Latimer, 2011

``Her Barnumesque publicity none of us could foresee. What we should have foreseen however, was that she would eventually tolerate no relationship that did not bring with it adulation. This was undoubtedly lacking in our otherwise entirely correct and cordial attitude towards her, so when the moment came to play the mad queen in public, our heads had to come off with the others, despite the very real service we had rendered her `{`in publishing her work`}`.``

Maria Jolas, 1935

``The most troubling narratives attempt to secure and aggrandize an ego-self understood to be separate from the rest of the world. Its supposed interests are pursued at the cost of others.``

David Loy, 2010

``Miss Gertrude Stein’s memoirs, published last year under the title of Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, having brought about a certain amount of controversial comment, Transition has opened its pages to several of those she mentions who, like ourselves, find that the book often lacks accuracy. This fact and the regrettable possibility that many less informed readers might accept Miss Stein’s testimony about her contemporaries, make it seem wiser to straighten out those points with which we are familiar before the book has had time to assume the character of historic authenticity. To MM. Henri Matisse, Tristan Tzara, Georges Braque, André Salmon we are happy to give the opportunity to refute those parts of Miss Stein’s book which they consider require it.``

Eugene Jolas, 1935

``Once a story is told, it ceases to be a story; it becomes a piece of history, an interpretive device.``

Carolyn Kay Steedman, 1986

``But for queer people, whose histories have typically been neither preserved nor celebrated, these links to the past, however imaginary, have great meaning. Creating a past not only validates the present, but makes the future imaginable.``

Tirza True Latimer, 2011

``To construct history...we need to search backwards from the vantage point of the present in order to appraise things in the past and attribute meaning to them. When events and entities in the past have been given their meaning in this way, then we can trace forward what we have already traced backwards, and make a history.``

Carolyn Kay Steedman, 1986

If Stein’s “genius” was not the legendary discovery of Picasso, Matisse, et al. and midwifing Modern Art, but was, in part, in producing “a web of international and interdisciplinary alliances, new schemas of kinship, new narratives of cultural value,” isn’t the genius actually that of contemporary scholars who excavate, interpret, highlight meaningful and life-affirming threads, and tell a story they call hers? And doesn’t genius also reside in those providing the organizational and financial resources for that story to be broadcast?

We have in “Seeing Gertrude Stein / Five Stories” a persuasive and invaluable retelling, and yet…

And yet even with the retelling we’re left with aspects of who she was that don’t fit neatly into a validating story of kinship and alliance, and that complicate her playing the iconic role for those among us seeking alternative modes of being and relating. Appropriation and retelling can be liberatory. But when an appropriation is also expropriation of another? When profoundly self-serving appropriation, without regard for the well-being of another, simultaneously disenfranchises…?

“Stein’s contradictions ran deep.”

Wanda M. Corn, 2011

Is it possible to host major exhibitions in flagship museums, to publish an elegant, deeply researched and insightfully written catalogue, and to plaster the city with Stein’s image, and not glorify her? Such a performance potentially lionizes Gertrude Stein, and that’s troubling.

Erasure has no place in a liberatory ethos.

Stories lend meaning to the vast, inchoate and tumultuous stuff of life. Living through stories is inherent to being human, so it isn’t a question of whether or not we tell, absorb and embody stories, but of whose stories we make our own. Evolution has favored embeddedness in community; living across the grain of that community can be thoroughly and excruciatingly unsettling. And yet, forcing a fit is a dis-ease because, interconnected as we may be, the prevailing story is never the whole story. The prevailing story’s insufficiencies disallow, erase and obliterate, and the imposition of its insufficiencies extinguishes life.

Whose stories do we make our own? To what extent is the importance we place on things a function of others’ storytelling? To what extent is value about others’ performances, about marketing, about promotion?

Without suggesting a diminishment of the importance of the stories that have been told and retold in “Seeing Gertrude Stein,” a sense of trouble remains. We must know that there is yet another story. It’s a story that doesn’t announce itself, but it is there for the hearing.

The story begins with “And…” Hearing beyond its opening line requires a shrugging “Who cares?” and turning away from the blazing and deafening performances of this or that community. And after turning away from, it requires turning in to, and attending.

“New York City is full of officially sanctioned artworks. Bless them all, and lucky us. At any given moment there are great quantities of them to be seen and enjoyed, clearly labeled, in museums, alternative spaces and art galleries, not to mention parks and plazas. But the city also has an abundance of inadvertent not-quite-art available for viewing, if you are open to it. These anonymous, unsung works are even more public. Especially in summer, when we tend to do more walking at a more leisurely pace, they lie in wait around just about every corner and down every street. Yet they are more private, too, since it is entirely up to us to recognize and appreciate them.”

Roberta Smith, 2011

“[Unconventional autobiographical] limit-cases constitute an alternative jurisdiction for self-representation in which writers relocate the grounds of judgment, install there a knowing subject rather than a sovereign or representative self, and produce an alternative jurisprudence about trauma, identity, and the forms both may take…Instead of an assertion of identity as that which makes sense within structures and relations marked by violence, limit-cases present identity as it develops against the grain of the sovereign self, the principles of law that underlie it, and the trauma they inflict and permit. The knowing self in contrast to the sovereign or representative self does not ask who am I, but how can the relations in which I live, dream, and act be reinvented through me.”

Leigh Gilmore, 2001

“What has praise and fame to do with poetry? What has seven editions (the book had already gone into no less) got to do with the value of it? Was not writing poetry a secret transaction, a voice answering a voice? So that all this chatter and praise and blame and meeting people who admired one and meeting people who did not admire one was as ill suited as could be to the thing itself–a voice answering a voice.”

Virginia Woolf, 1928

My heartfelt thanks to those who supported me in this event: Tyrell Collins, John Wood, Bob Conway, and Linda Lucero. And to Michelle Bertho, always.

Citations

(Wanda M. Corn, Seeing Gertrude Stein / Five Stories, 2011, p 215; quoting Leick, Gertrude Stein and the Making of an American Celebrity, 2009; quoting New York Herald Tribune Books, 1933.)

(Virginia Woolf, Women and Fiction, The Manuscript Versions of A Room of One’s Own, S. P. Rosenbaum, ed., 1992, p. 150.)

(Andermahr, Lovell, Wolkowitz, A Glossary of Feminist Theory, 2000, p. 191.)

(Tirza True Latimer, Seeing Gertrude Stein / Five Stories, 2011, p. 291.)

(Tristan Tzara, “Testimony Against Gertrude Stein,” Transition, 1935, p. 13.)

(Tirza True Latimer, Seeing Gertrude Stein / Five Stories, 2011, p. 330.)

(Maria Jolas, “Testimony Against Gertrude Stein," Transition, 1935, pp. 11-12.)

(David Loy, The World Is Made of Stories, 2010, p. 34.)

(Eugene Jolas, “Testimony Against Gertrude Stein,” Transition, 1935, p. 1.)

(Carolyn Kay Steedman, Landscape for a Good Woman, 1986, p. 143.)

(Tirza True Latimer, Seeing Gertrude Stein / Five Stories, 2011, p. 333.)

(Carolyn Kay Steedman, Landscape for a Good Woman, 1986, p. 21.)

(David Loy, The World Is Made of Stories, 2010, p. 5.)

(Leigh Gilmore, The Limits of Autobiography, 2001, p. 34.)

(Mark Freeman, “Rethinking the Fictive, Reclaiming the Real: Autobiography, Narrative Time, and the Burden of Truth,” Narrative and Consciousness, Fireman et al., 2003, p. 125.)

(Maria Jolas, “Testimony Against Gertrude Stein,” Transition, 1935, pp. 11-12.)

(David Loy, The World Is Made of Stories, 2010, pp. 25-26.)

(Wanda M. Corn, Seeing Gertrude Stein / Five Stories, 2011, p. 7.)

(Roberta Smith, “Around the Corner, Inadvertent Galleries,” The New York Times, August 24, 2011.)

(Leigh Gilmore, The Limits of Autobiography, 2001, pp. 143, 148.)

(Virginia Woolf, Orlando, 1928, p. 325.)